C

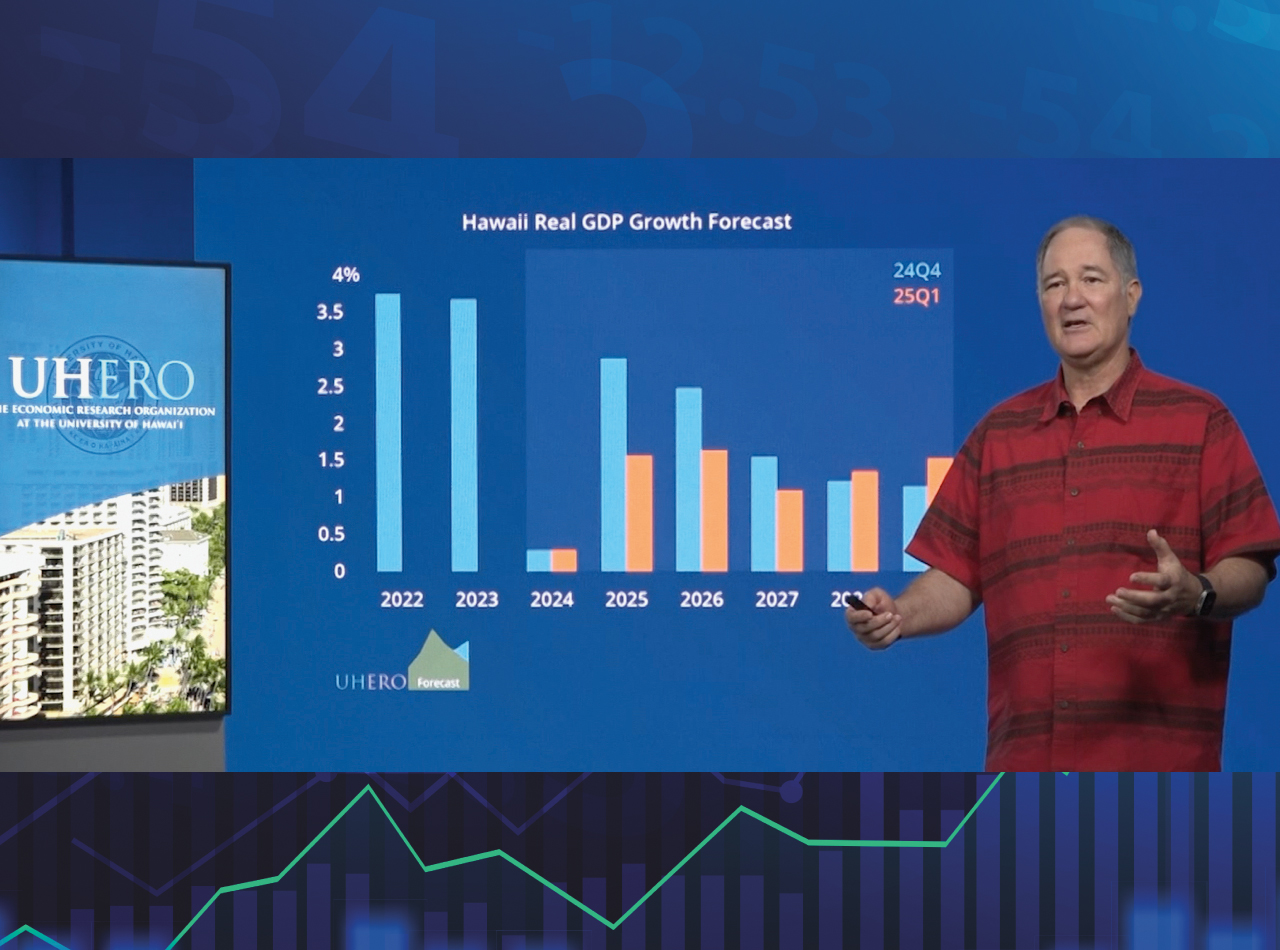

onstruction in Hawai‘i will continue to keep trucks on local roads, barges docking at Honolulu Harbor and cargo flights landing at Daniel K. Inouye International Airport. It’s a bright spot in the otherwise slow growth of the economy.

According to the Hawaii Department of Business, Economic Development and Tourism’s third quarter construction report, in the first half of 2024, private building authorizations in the state increased by $518.1 million — 29.8 percent — compared with the same period in 2023.

More projects mean more supplies.

“Many of the materials, supplies, equipment, goods are transported with trucks and drivers operating those trucks that make our life in Hawaii possible,” says Kelvin Kohatsu, managing director of the Hawaii Transportation Association. HTA serves as the trade organization of the local ground transportation industry, including delivery vehicles.

Despite its key role in keeping many sectors going forward, trucking faces challenges builders should be aware of. For example, legislation may affect the timeliness of projects in 2025.

“There may be some 2023-2024 bills that may reappear in the 2025 Legislative Session, [like] inheritance tax, transportation deregulation, commercial motor vehicles in the left lane, Commercial Driver’s License (CDL) changes … and more enforcement initiatives,” says Kohatsu.

While those are some immediate concerns, looming on the horizon is the state of Hawai‘i’s mandate of achieving net zero carbon emissions by 2045. When it comes to transportation, many see electric vehicles as part of the solution. But for cargo transport companies, that may not be viable.

“The trucking industry knows the BEV (battery electric vehicle) trucks are expensive to purchase and maintain,” Kohatsu says. BEVs are also range-challenged, lack a robust infrastructure to support charging and have issues regarding battery volatility. And perhaps most concerning is how much heavier BEVs are — directly affecting their hauling capacity.

A Snippet of Shipping Advice

Kimberly Ross, president of The Delivery People, says her company is anticipating “huge growth” in building supply shipments.

“Recently we started doing renovation projects for three different hotels in Maui,” she says. “We have upwards of 100 container projects already on the books for next year, also in Maui … not related to the fires.”

The Delivery People was originally founded in Maui as a cartage company. It’s now a comprehensive freight forwarding and delivery company, serving California, Hawaiʻi, Alaska, American Samoa, Guam and Puerto Rico.

With more construction in the islands and the need to use precious cargo spaces effectively, Ross offers the following tips to help builders:

Package Correctly: “We’ve run into a lot of issues where people are paying for a ton of extra space in a container because they built the pallets where they can’t put anything side-by-side and maybe can’t be stacked,” says Ross.

She recommends using specialists that can pack for different spaces in a variety of transports to be shipped efficiently and safely.

Understand Delivery Timelines: “If [your shipment] arrives early, it’s going to have to sit, and you’re going to have to pay for that. Or if it arrives late, you could potentially have delays,” she says.

An experienced transport company can help set up a shipping model that could minimize delays, meaning builders will “get a lot more bang for the buck.”

Work With Partners Who Know the Local Market: “I can’t advocate enough that it’s important that people have a local partner,” Ross says.

A mainland shipping company may not know that “big planes only fly into Honolulu” or “barges leave two days a week and they take this much time” or how to navigate “all these ins and outs of Hawaiʻi,” says Ross.

“I think it’s important that they partner with local people and companies that have an infrastructure in Hawaiʻi that can help guide them,”

she says.

A ‘PAYLOAD PREMIUM’

Pacific Transfer President and COO Christopher Redlew operates one of the largest tractor fleets in Hawai‘i.

“We’re doing more construction work just because of developing relationships with (firms) like Nan Inc. and Swinerton and such,” he says.

Redlew has reservations about electrification, explaining that Hawai‘i is a “small, family-based market,” making it unique.

“For the most part, there aren’t any major national truckers here servicing the piers. It’s all family-based, some California companies, but for the most part 95 percent of all companies are going to be family-owned in Hawai‘i, probably.”

These companies “just don’t have the capital” to replace their fleets with BEVs, he says.

“I’ve got 50 tractors on the road. We replace them at $165,000 (per unit),” Redlew says. “A few years back, pre-COVID, that was $120,000. So there’s no opportunity in which we would be able to start electrifying at over $400,000 a unit.”

BEVs can also be about 50 percent heavier than his standard vehicles. For example, Redlew’s typical tractor is about 16,000 pounds and an electric one could pile on another 7,000 pounds.

“The state’s not raising the gross vehicle weight that the roads are allowed for. It’s still 80,000 pounds,” he says.

If the state doesn’t raise GVW, Redlew would need to reduce his payloads to remain compliant. But that amounts to an economic hit.

“[Imagine saying to a customer,] ‘You guys got to take 7,000 pounds of freight out of your container because it’s too heavy because we’re using an electric tractor now.’ They’re not going to do that,” he explains.

Materials like masonry, roofing supplies and lumber are all “super heavy,” Redlew continues.

“That would have a major impact on construction costs because you have to take that out of the payload. That’s the payload premium.”

Kohatsu says the industry should look at other options.

“The better, more cost-effective approach is to utilize renewable fuels — biodiesel, renewable diesel, natural gas, renewable natural gas,” he says. “Present diesel engines are so much cleaner than they were just ten years ago.”

FUELING THE FUTURE

Pacific Air Cargo provides service daily between Los Angeles and Honolulu with connections to the neighbor islands and weekly services to Pago Pago and to Guam. As such, fuel is always a major concern, says Paul Skellon, the company’s director of marketing, communications and public relations.

“The aviation industry is doing a lot already, as far as sustainable aviation fuel (SAF),” he says. “A move to SAF is already underway, with international airlines such as Air New Zealand and Virgin Atlantic leading that innovation.”

The challenge is for the agricultural and refinery industries to be able to meet the demand for SAF, he says.

“Equipment and vehicle modernization away from gasoline and diesel would be an obvious move and we are seeing that slowly gaining ground in the industry,” says Skellon.

Electrification can make sense for equipment such as forklifts, smaller vehicles and tugs.

“I think we’ll see an increase in electric and hydrogen-powered vehicles and equipment as the industry moves to contribute to the state’s emission targets and timeline,” Skellon says. “But electrification of vehicles that work in the more heavy industry, things like trucks and heavy equipment, that hasn’t advanced as quickly as the domestic car has.”

And even then, electric vehicles still rely heavily on the grid.

“Unless the power is coming from wind or solar that is recharging your electric vehicles, all you’re doing is using more power out of the grid,” says Skellon. “We burn diesel fuel in Hawai‘i to produce electricity. It’s not sustainable.”

Hawai‘i needs to turn to itself, he implores.

“The lead needs to be taken by the state with offshore wind farms, for example, and wave energy, all of these things we have in abundance. That’s where the investment needs to be in the movement away from fossil fuels.”