Since 1967, Tileco Inc. on Hanua Street in Kapolei has served O‘ahu as a proven and dependable supplier of concrete and masonry goods.

Tasked with generating products so extensive — including standard concrete masonry units (CMU) of all shapes and sizes, various blocks, tiles and pavers that are glazed, colored and shaped to order, and grades of sand — Tileco remains flexible when it comes to providing solutions for both big and small projects statewide.

According to its website, Tileco’s full product line is available to everyone — from general contractors, landscapers and masonry companies to do-it-yourselfers building backyard waterfalls, raised garden beds and other home projects.

After Tileco’s products are pressurized, pigmented, baked, washed, polished and shrink-wrapped, water used in production is recycled with shovels and brooms helping to capture runaway aggregate, which eventually gets sent back to the production line.

Concrete blocks and tiles can be customized by Tileco according to pigment and gloss specifications.

PHOTO BY PAULA BENDER

Aggregate is pictured during the refining process at Tileco’s quarry yard in Hālawa. PHOTO BY PAULA BENDER

THREE GENERATIONS OF SAKAMOTOS

Tileco is a company with a legacy. Established by Richard Sakamoto in the 1960s, son Dennis Sakamoto started with the company as a laborer at 16 years old. Leanne Ogata, the third generation in the family business, serves as vice president and COO, while father Dennis is president and CEO.

Ogata joined the business in 2015 after graduating from the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa with a degree in civil engineering and minoring in business administration. These days, she’s all about the science of concrete.

“Leanne oversees the daily operations for a multi-million-dollar business that produces concrete masonry units,” says Lisa Kim, director of the Masonry Institute of Hawaii (MIH). “There are multiple tasks such as keeping the manufacturing process streamlined in terms of production volume, customizing block shape and colors, and scheduling shipments to the neighbor islands.”

As Masonry Institute of Hawaii director, Kim also has deep ties within Hawai‘i’s concrete and cement industries, and like the insurance industry, she’s a true believer in the advantages of non-combustible, fire-resistive cement-based construction.

According to the MIH website, materials like concrete masonry, precast concrete and cast-in-place concrete have many advantages beyond fire resistance, such as resistance to mold, vandalism and water damage. Additional benefits include reduced clean-up costs and quicker reoccupation.

Periodic checks of Tileco’s finished product are carried out before trucks are dispatched to jobsites. PHOTO BY PAULA BENDER

On Maui, Kūlanihāko’i High School in Kīhei is built with various products created at Tileco. PHOTO COURTESY KEITH KIDO/TILECO INC.

Tileco’s popular mortarless blocks, above, are ideal for landscaping. Pictured in the background are shrink-wrapped products ready for shipping.

PHOTO BY PAULA BENDER

QUARRIES PROVIDE PRODUCTS STATEWIDE

One company that’s an important resource for Tileco’s manufacturing production process is Hawaiian Cement, which maintains quarries and prodcution facilities in ‘Aiea, Hālawa and Kapolei on O‘ahu, in Kahului and Pu‘unene on Maui, in Hilo and Kamu‘ela on Hawai‘i island and in Līhu‘e on Kaua‘i.

In Hālawa Valley, miners in excavators high atop mountain ridges pound out basalt that’s loaded into giant dump trucks driven by Hawaiian Cement employees skilled in swiftly navigating the ups and downs of steeply graded roads hammered hard by heavy equipment in the area since 1939.

But is there gold in them hills? Actually, it’s only A- and B-grade basalt. A-grade is typically more dense and less weathered, while B-grade may contain voids and can be softer due to weathering. Different grades of aggregates are typically determined by physical properties, such as density and durability, and can vary from quarry to quarry.

PASS THE BASALT

According to Hawaiian Cement Quarry Supervisor Kevin McCary, A-grade aggregates are typically used for the production of ready-mix concrete, while B-grade is more commonly used in earthwork construction materials such as subgrades, base courses, drainage and pipe cushions.

Both A- and B-grade aggregates are also used for landscape beautification projects. The grades are not usually blended, as their applications are mostly independent of each other.

WET PROCESSING AND RECYCLING WATER

One silver lining for the Hālawa Valley quarry amid recent supply-chain issues is the performance of its wet processing plant, which was commissioned a few years ago with CDE Group.

Hawaiian Cement constantly works on improving its environmental record at its quarries, and its wet

processing system encompasses a variety of CDE-manufactured solutions, including an M4500 modular wash plant and an AggMax 250 logwasher, as well as an AquaCycle thickener that recycles the majority of water used.

The Hālawa Valley plant is currently producing up to 345 total petroleum hydrocarbons of aggregates used in Hawaiian Cement’s concrete products, comfortably meeting the monthly aggregate demand of 60,000 tons.

“I think it’s been three years now since we ordered any major components,” says Will Mason, a supervisor at the Hālawa quarry, referring to the wet processing system. “We have hiccups here and there, but nothing that can’t be fixed right away. The CDE guys react pretty fast when we need something, but we very seldom have issues with the plant. It sustains itself really well as far as productivity.”

Hawaiian Cement Hālawa Valley quarry Supervisor Kevin McCary, middle, explains how some of the company’s machinery is used in the washing and separation of aggregate. PHOTO BY PAULA BENDER

PREORDERING CEMENT

Hawaiian Cement customer service representatives can help contractors determine what is necessary by reviewing project specifications and building plans for any given project.

“For specialty items and homeowner requests, our qualified staff is happy to help through collaboration and asking the right questions to make sure their needs are fulfilled,” says McCary. “The design professional often crafts the specification with certain properties in mind and conveys that to the supplier. The supplier then meets those requirements with their expertise in concrete mix design.

“Suppliers may also make recommendations based on past experience with other similar projects or by learning about the application and construction methods. Many factors are considered such as exposure conditions, cost, construction practices and more to provide the best alternatives for the project,” he says.

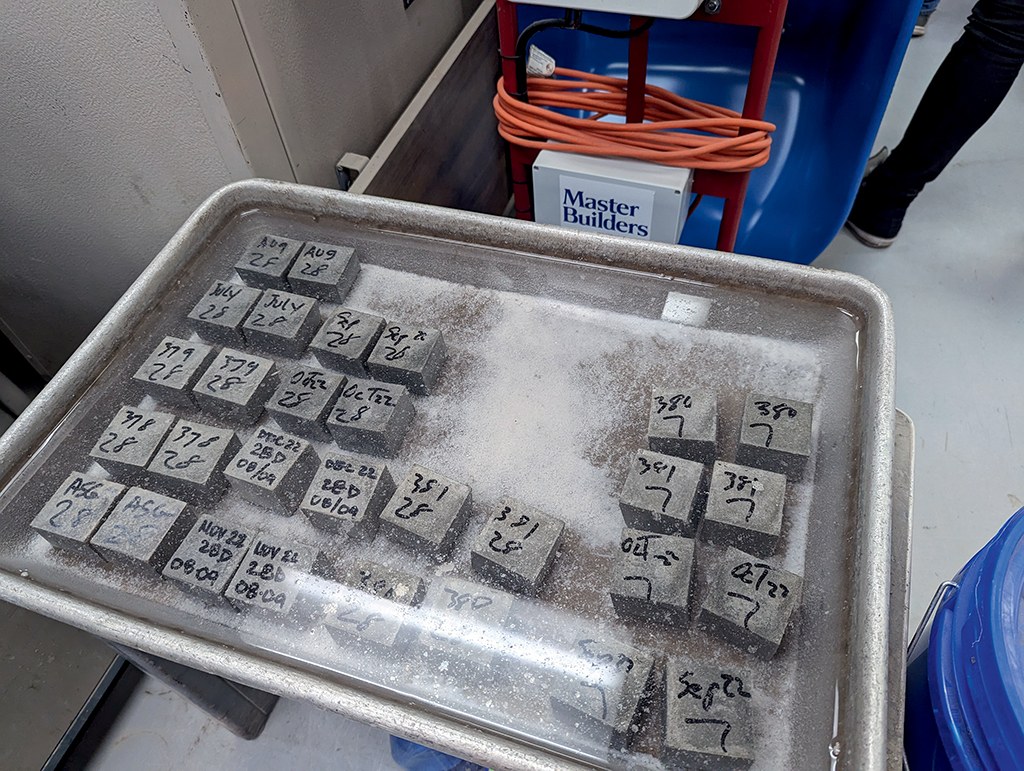

Samples of Hawaiian Cement’s different concrete formulas are pictured above in its Hālawa lab.

PHOTO BY PAULA BENDER

CONCRETE, CEMENT DEMANDS SKYROCKET ON RAIL PROJECT

One of the biggest projects currently using the lion’s share of concrete and cement is the Honolulu Authority for Rapid Transportation (HART) Skyline project.

McCary says the Hawai‘i concrete industry currently uses a Type I-II cement (fully portland cement) with plans to transition to a Type IL cement (a blend of portland cement with limestone) in the near future. (Cement is powder used as a binding ingredient in concrete.)

“For instance, although there is no difference in the cement used for HART and building construction, the concrete for HART differed from concrete used in buildings to allow for some of the flowability needed to achieve the patterns on the columns or the casting of the guideway segments, but was also similar by way of the materials used and some of the strengths required,” McCary says.

TESTING FOR FLEX

The requirements mentioned are all monitored by the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM), with ASTM International serving as a developer of voluntary consensus standards.

Flexural strength of concrete is determined by ASTM C78, or the “Standard Test Method for Flexural Strength of Concrete” in which ready-mix concrete is sampled and cast into 6-inch by 6-inch by 22-inch beam molds.

The beams are then stripped, cured, and placed in testing equipment that provides three-point loading to flex the beam until it breaks. The load rate of force applied to the beam is recorded, which is then converted to determine flexural strength.

“Many factors affect the flexural strength of concrete. Concrete performs best in compression. Most concrete designs include reinforcement where the strengths of each material complement each other to achieve the desired results,” McCary says.